Demodocus' Empty Chair

or, Poetry in the Era of the Digital Platform

For many years, I had been reluctant to go on social media – for all the obvious reasons. The ways these media encouraged instant, inconsiderate responses to events, rather than deliberate consideration, and their cramped formats, which likewise militated against serious thought, were deeply repugnant to me. As was the relentlessly abrasive stupidity of the greater portion of people frequenting these platforms. But as it has become nearly impossible for a writer these days to gain any attention for one’s work without the assistance of this technology, I have found myself using it more and more often out of necessity. And with this familiarity has come new reservations about the technology, and what it means for the possibility of writing in a manner that will prove adequate to the crises of our age.

One of the first things that anyone discovers when using these platforms is the way that increasing one’s exposure depends, at least at the outset, upon responding to pre-existing content. “Engagement” is all important; replies to and quotes of content that others have posted onto the platform is the necessary path one must take to garner attention for one’s own words. The obvious consequence of this functionality is that it limits the scope of thought for most users to whatever conversations are unfolding already. A new user who simply airs his thoughts on this or that will be opining into the ether for quite some time before anyone notices what he is up to. The technology is set up in such a way that it invites and rewards its users to think about what is already being thought about.

This is not to say that one cannot use the platform to air original ideas. In fact, social media has clearly provided an outlet for articulating and disseminating perspectives that challenge the hegemonic attitudes dominating other forms of media. If one looks around hard enough, one can find some extremely valuable and interesting work scattered across the various platforms, though generally at the margins of the most consuming topics of debate. My only point is that the technology is not set up to promote novel or unaligned perspectives on things. Rather, its basic tendency is to limit discourse to a set of prevalent conversations, and the assumed principles from which such conversations proceed.

One might respond that the technology only replicates in the digital sphere what has been a basic feature of civic life in all times and places, namely, a tendency of a given people to conduct their political, aesthetic, and religious controversies within a shared frame of assumptions and around a discrete number of topics. When Matthew Arnold and Thomas Huxley, in the latter portion of the 19th century, argued over the desired curriculum of an institution of higher learning, they were locking horns over a topic of central concern to their times: the respective truth claims of the humanities and modern science, and their appropriate roles in a course of study. Moreover, they could both take for granted a shared conception of the mission of the university – to equip burgeoning minds with the tools to make an adequate “criticism of life” – even if they disputed the best means of cultivating that adequacy. This common interest in a topic of unique urgency, debated within a framework of minimally shared assumptions, marks the normal contours of meaningful discourse throughout history.

But ours is no normal time, and no normal mode of discourse will suffice for its contingencies. The fact is that one can hardly point to any stable principles shared among a wide swath of the public, from which rational discourse can fruitfully proceed. Everything is up for grabs now. Not the regulative status of the concept of truth, not the desirability of beauty as an end of artistic creation, not the piety we owe to heritage and home – nothing can be taken for granted now. The cultural and spiritual deracination of the age, and the multiplied disorders it has occasioned in the various spheres of civilized life, have left us hardly any foundation upon which discourse can be grounded.

Moreover, the topics of contention that have entrenched themselves at the center of our squabbles invariably involve derivative and symptomatic, rather than fundamental, issues. The partisan bickering over the outrage of the day, though it demands a disproportionate amount of attention from the public, never gets at anything substantive in our culture, and so can never alter its basic conditions. Yet even beyond this politically aligned contention, the parameters of debate in our society tend to obscure, rather than illuminate, the patterns and habits of thought most decisively determining the spiritual conditions of the era. Issues like the altered conceptions of the church’s sacramental life or the rise in expressivist theories of artistic production, which cast momentous shadows over the intellectual potential of modern man, are never brought to light by the kinds of debates that dominate our cultural space.

The kinds of exertions capable of altering the cultural conditions of our times will have, as their most basic psychical orientation, an aspiration to reach beyond the prevalent modes and topics of conversation, as these are determined by the already existing state of our culture, towards an aboriginal encounter with reality that can inaugurate the kinds of conversation that encompass alternative visions of what our culture might be. Such a labor does not involve taking up the existing discourse, but grounding an entirely new form of discourse. It does not seek, dialectically, to arrange the conceptual apparatus provided by the age into propositions, but to invite, without possibility of affirmation or rebuttal, the listener into a shared perspective, characterized as a community of affection. In short, it is a work of founding.

I borrow the term from Heidegger, who uses it in his essay, “The Origin of the Work or Art.” There he writes: “the nature of art is poetry. The nature of poetry, in turn, is the founding of truth.” It is a founding of truth because its language “not only puts forth in words and statements what is overtly or covertly intended to be communicated” but “brings what is…into the Open for the first time.” As he puts it, “poetry is the saying of the unconcealedness of what is.” By disclosing the essence of things to the listener, poetry allows the listener to experience them for the first time. It “thrusts up the unfamiliar and extraordinary and at the same time thrusts down the ordinary and what we believe as such.” Such a novel and unexpected articulation of the parameters of experience can never be deduced in any logical manner from statements which have already been articulated. “The truth that discloses itself in the work can never be proved or derived from what went before.” Hence, the words of the poet, as Heidegger puts it in his essay “What are Poets For?” are “a saying other than the rest of human saying.”

This priority of poetic speech to the give and take of dialectical reasoning results from the poet’s ability to experience the world anew, or from a new perspective, unavailable to his contemporaries. His privilege is to speak of man’s fundamental relation to reality, borrowing from his age only the language necessary to make his insight communicable to them. As Heidegger’s own idol, the poet Friedrich Holderlin, puts it:

In that the poet feels himself seized in his whole inner and outer life by the pure tone of his original sensation and he looks about him in his world, it is new and unknown to him, the sum of all his experiences, his knowledge, his intuitions and memories, art and nature, as it presents itself within and without him; everything is present to him as if for the first time, for this very reason ungrasped, undetermined, dissolved into sheer material and life. And it is supremely important that he does not at this moment accept anything as given, does not start from anything positive, that nature and art, as he has learned to know and see them, do not speak before a language is there for him

Marcel Detienne, in his study The Masters of Truth in Archaic Greece, recounts the cultural history whereby this privileged and excluded “saying” of the poet eventually loses its purchase and surrenders its claims to the supremacy of dialectic. The speech of the poet is marked by a kind of efficacy, or krainein, which “establishes reality” through its force and power. Detienne makes it clear that this power obviates all the conventions of discursive reasoning:

The Poet’s speech never solicits agreement from its listeners or assent from a social group, no more than does a king of justice: it is deployed with all the majesty of oracular speech. It does not attempt to establish a chain of words in real time that would gather force from human approval or disagreement.

Undoubtedly, the power of a language that resists rational assessment and contention is an ambiguous one, a power that can readily be used for the expression of truth and falsity alike. Thus the Muses in Hesiod’s Theogony proclaim, “We know how to say many false things that seem like true sayings, but we know also how to speak the truth when we wish to.”

This ambiguity eventually seeks resolution in the give and take of debate among warriors in assembly. Characteristically, such assemblies gathered a “group of equals,” who enjoy an “equal right of speech.” No special reverence is reserved for the station of the poet and the words which emanate from that station; rather, “assemblies are open to all warriors, all who fully exercise the profession of arms,” and therefore, “speech is not the privilege solely of an exceptional man possessing religious powers.” Inevitably, this equality among participants in debate results in the subjection of speech to argumentative assessment: “(dialogue-speech) is founded in essence on social agreement manifested as either approval or disapproval. In such military assemblies, the value of the speech for the first time depended on the judgment of the social group as a whole.” Detienne makes it clear that this is the mode of speech which prevails within the polis; once entered into political society, men must speak of what their fellows speak of, and endure the appraisal of their contemporaries upon their speech.

The cost of this equal speech is a forfeiture of language’s traffic with the divine, and its demotion to exclusive concern with “human affairs, affairs that concern every member of the group in his relations with his comrades.” By withholding the transcendent dimensions of human life from a society’s view, and obscuring the fundamental issues impinging upon human existence, dialogue-speech confines its members’ thoughts to the prevalent conversations. When those conversations are narrow enough, when the principles of judgment employed in them are degraded enough, the possibility of speaking words adequate to the age is foreclosed, and the people have arrived at their crisis. Introduce a technology that exacerbates this dynamic many, many times over, and you engender the crisis of our own age.

Our need for the particular ministrations of poetry is therefore acute – for its capacity to ground new conversations, to incubate new standards of judgment. The dilemma confronting the poet of our own age, however, is that the fora in which he must present his work and his vision are reliant upon certain forms of technology, which have their own meaning. We live in an age when all speech is mediated electronically, and the poet’s speech is no exception. The technology that platforms speech has been designed with certain ends in mind, by certain people holding certain views about the world, and these preconditions inevitably determine the form and content of the speech presented there. The poet of our age always faces the threat that the significance and impact of his work will be vitiated by the very medium he must resort to in order to disseminate it.

We have seen how, in the case of social media, the tendency of the technology was to counteract the most distinctive characteristic of poetic speech, which is its power to liberate our attention from the prevalent conversations of our society and ground new conversations in the permanent dimensions of human experience. Social media privileges the speaker who speaks about what everyone else is speaking about, and so tends to foreclose the poet’s aspirations to found new modes of discourse. And of course, this is only one tendency of the technology, and social media is only one example of the technology that constitutes the necessary fora of the contemporary poet.

I am not dismissing the possibility of a poet utilizing these media in ways that are conducive to his art, nor I am discounting the tremendous reach and exposure which they potentially offer him. I only wish to make the point that the determinate nature of the technology through which the contemporary poet is compelled to address his audience, and the separate significance imparted to his chosen forum by the designer of that technology, are concerns of a novel and unique nature which previous generations of poets did not need to confront, but which must occupy this generation intently. The words of the poet in our age must be mediated by a technology that has its origin in separate, and perhaps conflicting, aspirations of the soul than those that give rise to his artistry. To practice the art in our time is to be mindful of the compromised nature of the fora in which the poetic utterance must be presented.

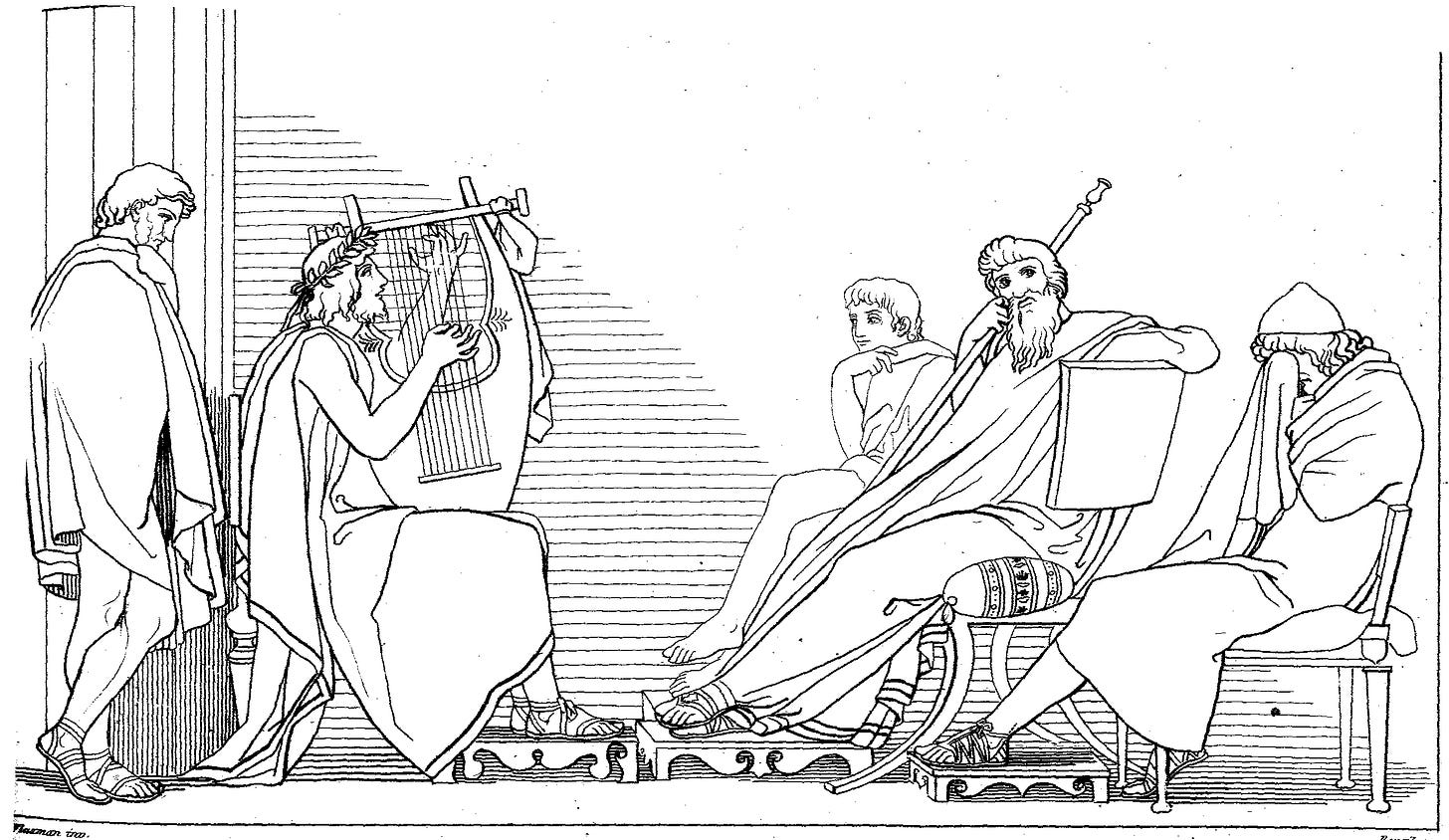

The nature of the contemporary poet’s changed condition can be appreciated by examining the first appearance of the poet in our literature, in Book 8 of the Odyssey. There, the blind bard Demodocus is led reverently into the court of Alcinous, where the assembled nobles have gathered to honor the presence of their visitor. Seated on a “silver studded chair in the midst of the banqueters,” he takes down his lyre, and begins to sing of “the glorious deeds of warriors.” His words go directly to the ears and hearts of his listeners, his fora is determined by their unmediated presence, and thus, as the king himself declares, he may “give delight in whatever way his spirit prompts him to sing.”

It is many ages since the poet has sat comfortably upon the chair of Demodocus, and enjoyed the privilege of singing exactly how his spirit dictates, without consideration for the structure and limitations of the forum in which he sings. The theater and the codex have already, for many, many generations, determined the form and content of poetic utterance through their own technological imperatives. But the prevalence of those imperatives over the electronically mediated word is of an entirely different order, and beset the modern poet with an entirely different set of challenges. These he must confront directly, knowingly, confident in the divine origins of his art, in whatever way it appears.